18 Overview of the Multitenant Architecture

This section contains the following topics:

Overview of Containers in a CDB

A container is a collection of schemas, objects, and related structures in a multitenant container database (CDB) that appears logically to an application as a separate database. Within a CDB, each container has a unique ID and name.

The root and every pluggable database (PDB) is considered a container. PDBs isolate data and operations so that from the perspective of a user or application, each PDB appears as if it were a traditional non-CDB.

This section contains the following topics:

The Root

The root container, also called the root, is a collection of schemas, schema objects, and nonschema objects to which all PDBs belong. Every CDB has one and only one root container, named CDB$ROOT, which stores the system metadata required to manage PDBs. All PDBs belong to the root.

The root does not store user data. Thus, you must not add user data to the root or modify system-supplied schemas in the root. However, you can create common users and roles for database administration (see "Common Users in a CDB"). A common user with the necessary privileges can switch between PDBs.

See Also:

PDBs

A PDB is a user-created set of schemas, objects, and related structures that appears logically to an application as a separate database. Every PDB is owned by SYS, which is a common user in the CDB (see "Common Users in a CDB"), regardless of which user created the PDB.

This section contains the following topics:

Purpose of PDBs

You can use PDBs to achieve the following goals:

-

Store data specific to a particular application

For example, a sales application can have its own dedicated PDB, and a human resources application can have its own dedicated PDB.

-

Move data into a different CDB

A database is "pluggable" because you can package it as a self-contained unit, and then move it into another CDB.

-

Isolate grants within PDBs

A local or common user with appropriate privileges can grant

EXECUTEprivileges on a package toPUBLICwithin an individual PDB.

Names for PDBs

PDBs must be uniquely named within a CDB, and follow the same naming rules as service names. Moreover, because a PDB has a service with its own name, a PDB name must be unique across all CDBs whose services are exposed through a specific listener.

The first character of a user-created PDB name must be alphanumeric, with remaining characters either alphanumeric or an underscore (_). Because service names are case-insensitive, PDB names are case-insensitive, and are in upper case even if specified using delimited identifiers.

See Also:

Oracle Database Net Services Reference for the rules for service names

Scope for Names and Privileges in PDBs

PDBs have separate namespaces, which has implications for the following structures:

-

Schemas

A schema contained in one PDB may have the same name as a schema in a different PDB. These two schemas may represent distinct local users, distinguished by the PDB in which the user name is resolved at connect time, or a common user (see "Overview of Common and Local Users in a CDB").

-

Objects

An object must be uniquely named within a PDB, not across all containers in the CDB. This is true both of schema objects and nonschema objects. Identically named database objects and other dictionary objects contained in different PDBs are distinct from one another.

An Oracle Database directory is an example of a nonschema object. In a CDB, common user

SYSowns directories. Because each PDB has its ownSYSschema, directories belong to a PDB by being created in theSYSschema of the PDB.

During name resolution, the database consults only the data dictionary of the container to which the user is connected. This behavior applies to object names, the PUBLIC schema, and schema names.

Database Links Between PDBs

In a CDB, all database objects reside in a schema, which in turn resides in a container. Because PDBs appear to users as non-CDBs, schemas must be uniquely named within a container but not across containers. For example, the rep schema can exist in both salespdb and hrpdb. The two schemas are independent (see Figure 18-7 for an example).

A user connected to one PDB must use database links to access objects in a different PDB. This behavior is directly analogous to a user in a non-CDB accessing objects in a different non-CDB.

See Also:

Oracle Database Administrator's Guide to learn how to access objects in other PDBs using database links

Data Dictionary Architecture in a CDB

From the user and application perspective, the data dictionary in each container in a CDB is separate, as it would be in a non-CDB. For example, the DBA_OBJECTS view in each PDB can show a different number of rows. This dictionary separation enables Oracle Database to manage the PDBs separately from each other and from the root.

Purpose of Data Dictionary Separation

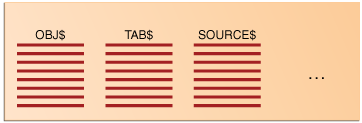

In a newly created non-CDB that does not yet contain user data, the data dictionary contains only system metadata. For example, the TAB$ table contains rows that describe only Oracle-supplied tables, for example, TRIGGER$ and SERVICE$.

The following graphic depicts three underlying data dictionary tables, with the red bars indicating rows describing the system.

Figure 18-1 Unmixed Data Dictionary Metadata in a Non-CDB

Description of "Figure 18-1 Unmixed Data Dictionary Metadata in a Non-CDB"

If users create their own schemas and tables in this non-CDB, then the data dictionary now contains some rows that describe Oracle-supplied entities, and other rows that describe user-created entities. For example, the TAB$ dictionary table now has a row describing employees and a row describing departments.

Figure 18-2 Mixed Data Dictionary Metadata in a Non-CDB

Description of "Figure 18-2 Mixed Data Dictionary Metadata in a Non-CDB"

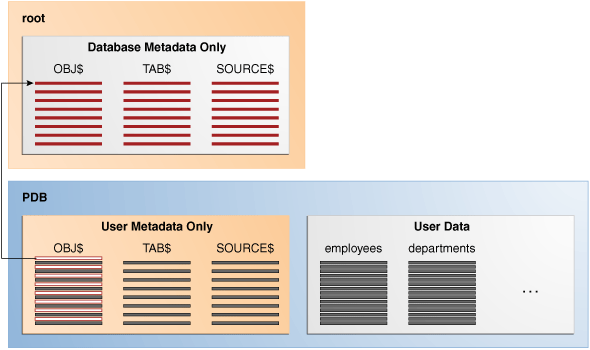

In a CDB, the data dictionary metadata is split between the root and the PDBs. In the following figure, the employees and departments tables reside in a PDB. The data dictionary for this user data also resides in the PDB. Thus, the TAB$ table in the PDB has a row for the employees table and a row for the departments table.

Figure 18-3 Data Dictionary Architecture in a CDB

Description of "Figure 18-3 Data Dictionary Architecture in a CDB"

The preceding graphic shows that the data dictionary in the PDB contains pointers to the data dictionary in the root. Internally, Oracle-supplied objects such as data dictionary table definitions and PL/SQL packages are represented only in the root. This architecture achieves two main goals within the CDB:

-

Reduction of duplication

For example, instead of storing the source code for the

DBMS_ADVISORPL/SQL package in every PDB, the CDB stores it only inCDB$ROOT, which saves disk space. -

Ease of database upgrade

If the definition of a data dictionary table existed in every PDB, and if the definition were to change in a new release, then each PDB would need to be upgraded separately to capture the change. Storing the table definition only once in the root eliminates this problem.

Metadata and Object Links in the CDB Root

The CDB uses an internal mechanism to separate data dictionary information.

Specifically, Oracle Database uses the following automatically managed pointers:

-

Metadata links

Oracle Database stores metadata about dictionary objects only in the root. For example, the column definitions for the

OBJ$dictionary table, which underlies theDBA_OBJECTSdata dictionary view, exist only in the root. As depicted in Figure 18-3, theOBJ$table in each PDB uses an internal mechanism called a metadata link to point to the definition ofOBJ$stored in the root.The data corresponding to a metadata link resides in its PDB, not in the root. For example, if you create table

mytableinhrpdband add rows to it, then the rows are stored in the PDB files. The data dictionary views in the PDB and in the root contain different rows. For example, a new row describingmytableexists in theOBJ$table inhrpdb, but not in theOBJ$table in the root. Thus, a query ofDBA_OBJECTSin the root andDBA_OBJECTSinhrdpbshows different result sets. -

Object links

In some cases, Oracle Database stores the data (not metadata) for an object only once in the root. For example, AWR data resides in the root. Each PDB uses an internal mechanism called an object link to point to the AWR data in the root, thereby making views such as

DBA_HIST_ACTIVE_SESS_HISTORYandDBA_HIST_BASELINEaccessible in each separate container.

Oracle Database automatically creates and manages object and metadata links. Users cannot add, modify, or remove these links.

Container Data Objects in a CDB

A container data object is a table or view containing data pertaining to multiple containers and possibly the CDB as a whole, along with mechanisms to restrict data visible to specific common users through such objects to one or more containers. Examples of container data objects are Oracle-supplied views whose names begin with V$ and CDB_.

All container data objects have a CON_ID column. The following table shows the meaning of the values for this column.

Table 18-1 Container ID Values

| Container ID | Rows pertain to |

|---|---|

|

|

Whole CDB, or non-CDB |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

All Other IDs |

User-Created PDBs |

In a CDB, for every DBA_ view, a corresponding CDB_ view exists. The owner of a CDB_ view is the owner of the corresponding DBA_ view. The following figure shows the relationship among the different categories of dictionary views.

Figure 18-4 Dictionary View Relationships in a CDB

Description of "Figure 18-4 Dictionary View Relationships in a CDB"

When the current container is a PDB, a user can view data dictionary information for the current PDB only. To an application connected to a PDB, the data dictionary appears as it would for a non-CDB. When the current container is the root, however, a common user can query CDB_ views to see metadata for the root and for PDBs for which this user is privileged.

The following table shows a scenario involving queries of CDB_ views. Each row describes an action that occurs after the action in the preceding row.

Table 18-2 Querying CDB_ Views

| Operation | Description |

|---|---|

SQL> CONNECT SYSTEM Enter password: ******** Connected. |

The |

SQL> SELECT COUNT(*) FROM CDB_USERS

WHERE CON_ID=1;

COUNT(*)

--------

41

|

|

SQL> SELECT COUNT(DISTINCT(CON_ID))

FROM CDB_USERS;

COUNT(DISTINCT(CON_ID))

-----------------------

4

|

|

SQL> CONNECT SYSTEM@hrdb Enter password: ******** Connected. |

The |

SQL> SELECT COUNT(*) FROM CDB_USERS;

COUNT(*)

----------

45

|

|

Data Dictionary Storage in a CDB

The data dictionary that stores the metadata for the CDB as a whole is stored only in the system tablespaces. The data dictionary that stores the metadata for a specific PDB is stored in the self-contained tablespaces dedicated to this PDB. The PDB tablespaces contain both the data and metadata for an application back end. Thus, each set of data dictionary tables is stored in its own dedicated set of tablespaces.

See Also:

Current Container

For a given session, the current container is the one in which the session is running. The current container can be the root (for common users only) or a PDB.

Each session has exactly one current container at any point in time. Because the data dictionary in each container is separate, Oracle Databases uses the data dictionary in the current container for name resolution and privilege authorization.

See Also:

Oracle Database Administrator's Guide to learn more about the current container

Cross-Container Operations

A cross-container operation is a DDL statement that affects any of the following:

-

The CDB itself

-

Multiple containers

-

Multiple entities such as common users or common roles that are represented in multiple containers

-

A container different from the one to which the user issuing the DDL statement is currently connected

Only a common user connected to the root can perform cross-container operations (see "Common Users in a CDB"). Examples include user SYSTEM granting a privilege commonly to another common user (see "Roles and Privileges Granted Commonly in a CDB"), and an ALTER DATABASE . . . RECOVER statement that applies to the entire CDB.

See Also:

Overview of Services in a CDB

Clients must connect to PDBs using services. A connection using a service name starts a new session in a PDB. A foreground process, and therefore a session, at every moment of its lifetime, has a uniquely defined current container.

The following figure shows two clients connecting to PDBs using two different listeners.

Service Creation in a CDB

When you create a PDB, the database automatically creates and starts a service inside the CDB. The service has a property, shown in the DBA_SERVICES.PDB column, that identifies the PDB as the initial current container for the service. The service has the same name as the PDB. The PDB name must be a valid service name, and must be unique within the CDB. For example, in Figure 18-5 the PDB named hrpdb has a default service named hrpdb. The default service must not be dropped.

You can create additional services for each PDB. Each additional service denotes its PDB as the initial current container. In Figure 18-5, nondefault services exist for erppdb and hrpdb. Create, maintain, and drop additional services using the same techniques that you use in a non-CDB.

Note:

When two or more CDBs on the same computer system use the same listener, and two or more PDBs have the same service name in these CDBs, a connection that specifies this service name connects randomly to one of the PDBs with the service name. To avoid incorrect connections, ensure that all service names for PDBs are unique on the computer system, or configure a separate listener for each CDB on the computer system.

See Also:

-

Oracle Database Administrator's Guide to learn how to manage services associated with PDBs

Connections to Containers in a CDB

A CDB administrator with the appropriate privileges can connect to any container in the CDB. The administrator can use either of the following techniques:

-

Use the

ALTER SESSION SET CONTAINERstatement, which is useful for both connection pooling and advanced CDB administration, to switch between containers.For example, a CDB administrator can connect to the root in one session, and then in the same session switch to a PDB. In this case, the user requires the

SET CONTAINERsystem privilege in the container. -

Connect directly to a PDB.

In this case, the user requires the

CREATE SESSIONprivilege in the container.

Table 18-3 describes a scenario involving the CDB in Figure 18-5. Each row describes an action that occurs after the action in the preceding row. Common user SYSTEM queries the name of the current container and the names of PDBs in the CDB.

Table 18-3 Services in a CDB

| Operation | Description |

|---|---|

SQL> CONNECT SYSTEM@prod Enter password: ******** Connected. |

The |

SQL> SHOW CON_NAME CON_NAME -------- CDB$ROOT |

|

SQL> SELECT NAME, PDB FROM V$SERVICES ORDER BY PDB, NAME; NAME PDB ---------------------- -------- SYS$BACKGROUND CDB$ROOT SYS$USERS CDB$ROOT prod.example.com CDB$ROOT erppdb.example.com ERPPDB erp.example.com ERPPDB hr.example.com HRPDB hrpdb.example.com HRPDB salespdb.example.com SALESPDB 8 rows selected. |

A query of |

SQL> ALTER SESSION SET CONTAINER = hrpdb; Session altered. |

|

SQL> SELECT

SYS_CONTEXT('USERENV', 'CON_NAME')

AS CUR_CONTAINER FROM DUAL;

CUR_CONTAINER

-------------

HRPDB

|

A query confirms that the current container is now |

See Also:

Oracle Database Administrator's Guide to learn how to connect to PDBs

Overview of Commonality in a CDB

In a CDB, the basic principle of commonality is that a common phenomenon is the same in every existing and future container. In a CDB, "common" means "common to all containers." In contrast, a local phenomenon is restricted to exactly one existing container.

A corollary to the principle of commonality is that only a common user can alter the existence of common phenomena. More precisely, only a common user connected to the root can create, destroy, or modify CDB-wide attributes of a common user or role.

This section contains the following topics:

Overview of Common and Local Users in a CDB

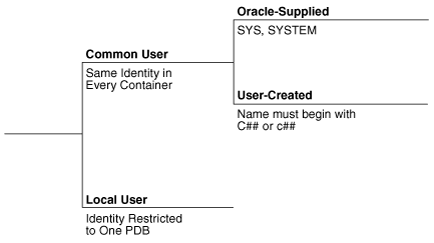

Every user that owns objects that define the database is common. User-created users are either local or common. Figure 18-6 shows the possible user types in a CDB.

Common Users in a CDB

A common user is a database user that has the same identity in the root and in every existing and future PDB. Every common user can connect to and perform operations within the root, and within any PDB in which it has privileges.

Every common user is either Oracle-supplied or user-created. Examples of Oracle-supplied common users are SYS and SYSTEM.

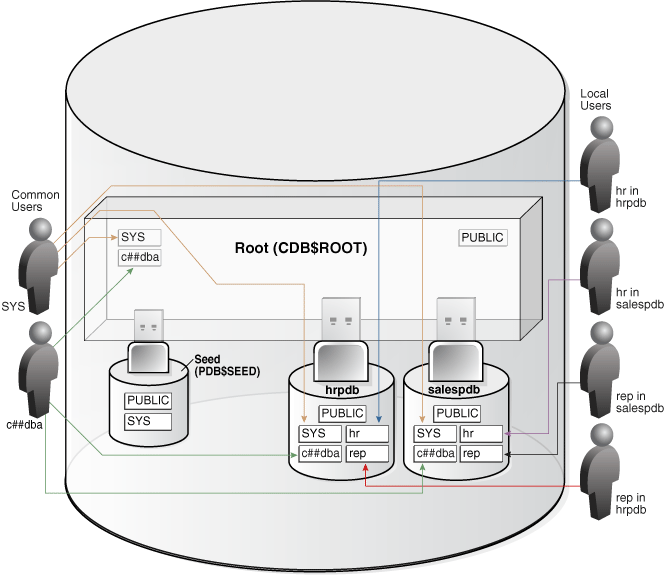

Figure 18-7 shows sample users and schemas in two PDBs: hrpdb and salespdb. SYS and c##dba are common users who have schemas in CDB$ROOT, hrpdb, and salespdb. Local users hr and rep exist in hrpdb. Local users hr and rep also exist in salespdb.

Common users have the following characteristics:

-

A common user can log in to any container (including

CDB$ROOT) in which it has theCREATE SESSIONprivilege.A common user need not have the same privileges in every container. For example, the

c##dbauser may have the privilege to create a session inhrpdband in the root, but not to create a session insalespdb. Because a common user with the appropriate privileges can switch between containers, a common user in the root can administer PDBs. -

The name of every user-created common user must begin with the characters

c##orC##. (Oracle-supplied common user names do not have this restriction.)No local user name may begin with the characters

c##orC##. -

The names of common users must contain only ASCII or EBCDIC characters.

-

Every common user is uniquely named across all containers.

A common user resides in the root, but must be able to connect to every PDB with the same identity.

-

The schemas for a common user can differ in each container.

For example, if

c##dbais a common user that has privileges on multiple containers, then thec##dbaschema in each of these containers may contain different objects.

See Also:

Oracle Database Security Guide to learn about common and local accounts

Local Users in a CDB

A local user is a database user that is not common and can operate only within a single PDB. Local users have the following characteristics:

-

A local user is specific to a particular PDB and owns a schema in this PDB.

In Figure 18-7, local user

hronhrpdbowns thehrschema. Onsalespdb, local userrepowns therepschema, and local userhrowns thehrschema.A local user cannot be created in the root.

-

A local user on one PDB cannot log in to another PDB or to the root.

When

hrconnects tohrpdb,hrcannot access objects in theshschema that reside in thesalespdbdatabase without using a database link. In the same way, whenshconnects to thesalespdbPDB,shcannot access objects in thehrschema that resides inhrpdbwithout using a database link. -

The name of a local user must not begin with the characters

c##orC##. -

The name of a local user must only be unique within its PDB.

The user name and the PDB in which that user schema is contained determine a unique local user. Figure 18-7 shows that a local user and schema named

repexist onhrpdb. A completely independent local user and schema namedrepexist on thesalespdbPDB. -

Whether local users can access objects in a common schema depends on their user privileges.

For example, the

c##dbacommon user may create a table in thec##dbaschema onhrpdb. Unlessc##dbagrants the necessary privileges to the localhruser on this table,hrcannot access it.

Table 18-4 describes a scenario involving the CDB in Figure 18-7. Each row describes an action that occurs after the action in the preceding row. Common user SYSTEM creates local users in two PDBs.

Table 18-4 Local Users in a CDB

| Operation | Description |

|---|---|

SQL> CONNECT SYSTEM@hrpdb Enter password: ******** Connected. |

|

SQL> CREATE USER rep IDENTIFIED BY password;

User created.

SQL> GRANT CREATE SESSION TO rep;

Grant succeeded.

|

|

SQL> CONNECT rep@salespdb Enter password: ******* ERROR: ORA-01017: invalid username/password; logon denied |

The |

SQL> CONNECT SYSTEM@salespdb Enter password: ******** Connected. |

|

SQL> CREATE USER rep IDENTIFIED BY password;

User created.

SQL> GRANT CREATE SESSION TO rep;

Grant succeeded.

|

|

SQL> CONNECT rep@salespdb Enter password: ******* Connected. |

The |

See Also:

Oracle Database Security Guide to learn about local accounts

Overview of Common and Local Roles in a CDB

Every Oracle-supplied role is common. In Oracle-supplied scripts, every privilege or role granted to Oracle-supplied users and roles is granted commonly, with one exception: system privileges are granted locally to the common role PUBLIC (see "Grants to PUBLIC in a CDB"). User-created roles are either local or common.

Common Roles in a CDB

A common role is a database role that exists in the root and in every existing and future PDB. Common roles are useful for cross-container operations (see "Cross-Container Operations"), ensuring that a common user has a role in every container.

Every common role is either user-created or Oracle-supplied. All Oracle-supplied roles are common, such as DBA and PUBLIC. User-created common roles must have names starting with C## or c##, and must contain only ASCII or EBCDIC characters. For example, a CDB administrator might create common user c##dba, and then grant the DBA role commonly to this user, so that c##dba has the DBA role in any existing and future PDB.

A user can only perform common operations on a common role, for example, granting privileges commonly to the role, when the following criteria are met:

-

The user is a common user whose current container is root.

-

The user has the

SET CONTAINERprivilege granted commonly, which means that the privilege applies in all containers. -

The user has privilege controlling the ability to perform the specified operation, and this privilege has been granted commonly (see "Roles and Privileges Granted Commonly in a CDB").

For example, to create a common role, a common user must have the CREATE ROLE and the SET CONTAINER privileges granted commonly. In the CREATE ROLE statement, the CONTAINER=ALL clause specifies that the role is common.

See Also:

-

Oracle Database Security Guide to learn how to manage common roles

-

Oracle Database SQL Language Reference to learn about the

CREATE ROLEstatement

Local Roles in a CDB

A local role exists only in a single PDB, just as a role in a non-CDB exists only in the non-CDB. A local role can only contain roles and privileges that apply within the container in which the role exists.

PDBs in the same CDB may contain local roles with the same name. For example, the user-created role pdbadmin may exist in both hrpdb and salespdb. These roles are completely independent of each other, just as they would be in separate non-CDBs.

See Also:

Oracle Database Security Guide to learn how to manage local roles

Overview of Privilege and Role Grants in a CDB

Just as in a non-CDB, users in a CDB can grant roles and privileges. A key difference in a CDB is the distinction between roles and privileges that are locally granted and commonly granted. A privilege or role granted locally is exercisable only in the container in which it was granted. A privilege or role granted commonly is exercisable in every existing and future container.

Users and roles may be common or local. However, a privilege is in itself neither common nor local. If a user grants a privilege locally using the CONTAINER=CURRENT clause, then the grantee has a privilege exercisable only in the current container. If a user grants a privilege commonly using the CONTAINER=ALL clause, then the grantee has a privilege exercisable in any existing and future container.

Principles of Privilege and Role Grants in a CDB

In a CDB, every act of granting, whether local or common, occurs within a specific container.

The basic principles of granting are as follows:

-

Both common and local phenomena may grant and be granted locally.

-

Only common phenomena may grant or be granted commonly.

Local users, roles, and privileges are by definition restricted to a particular container. Thus, local users may not grant roles and privileges commonly, and local roles and privileges may not be granted commonly.

The following figure illustrates these principles. In the top, a common user commonly grants a role or privilege to a common user or role. Consequently, the grant recipient has the privilege or role (p/r box) in all containers.

In the bottom section of the diagram, local users (L boxes) and common users (C boxes) make local grants to one another. Consequently, each user receives a grant of a privilege or role (p/r box) that is restricted to the container in which the grant occurred. The local grants have no applicability to common or local users and roles in other containers.

The following sections describe the implications of the preceding principles.

Privileges and Roles Granted Locally in a CDB

Roles and privileges may be granted locally to users and roles regardless of whether the grantees, grantors, or roles being granted are local or common. Table 18-5 explains the valid possibilities for locally granted roles and privileges.

What Makes a Grant Local

A role or privilege is granted locally when the following criteria are met:

-

The grantor has the necessary privileges to grant the specified role or privileges.

For system roles and privileges, the grantor must have the

ADMINOPTIONfor the role or privilege being granted. For object privileges, the grantor must have theGRANTOPTIONfor the privilege being granted. -

The grant applies to only one container.

By default, the

GRANTstatement includes theCONTAINER=CURRENTclause, which indicates that the privilege or role is being granted locally.

Roles and Privileges Granted Locally

A user or role may be locally granted a privilege (CONTAINER=CURRENT). For example, a READ ANY TABLE privilege granted locally to a local or common user in hrpdb applies only to this user in this PDB. Analogously, the READ ANY TABLE privilege granted to user hr in a non-CDB has no bearing on the privileges of an hr user that exists in a separate non-CDB.

A user or role may be locally granted a role (CONTAINER=CURRENT). As shown in Table 18-5, a common role may receive a privilege granted locally. For example, the common role c##dba may be granted the READ ANY TABLE privilege locally in hrpdb. If the c##cdb common role is granted locally, then privileges in the role apply only in the container in which the role is granted. In this example, a common user who has the c##cdba role does not, because of a privilege granted locally to this role in hrpdb, have the right to exercise this privilege in any PDB other than hrpdb.

See Also:

Oracle Database Security Guide to learn how to grant roles and privileges in a CDB

Roles and Privileges Granted Commonly in a CDB

Privileges and common roles may be granted commonly. According to the principles of granting in a CDB, users or roles may be granted roles and privileges commonly only if the grantees and grantors are both common; and if a role is being granted commonly, then the role itself must be common. Table 18-6 explains the possibilities for common grants.

Table 18-6 Common Grants

| Phenomenon | May Grant Commonly | May Be Granted Commonly | May Receive Roles and Privileges Granted Commonly |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Common User |

Yes |

N/A |

Yes |

|

Local User |

No |

N/A |

No |

|

Common Role |

N/A |

Yes3 |

Yes |

|

Local Role |

N/A |

No |

No |

|

Privilege |

N/A |

Yes |

N/A |

What Makes a Grant Common

A role or privilege is granted commonly when the following criteria are met:

-

The grantor is a common user.

-

The grantee is a common user or common role.

-

The grantor has the necessary privileges to grant the specified role or privileges.

For system roles and privileges, the grantor must have the

ADMINOPTIONfor the role or privilege being granted. For object privileges, the grantor must have theGRANTOPTIONfor the privilege being granted. -

The grant applies to all containers.

The

GRANTstatement includes aCONTAINER=ALLclause specifying that the privilege or role is being granted commonly. -

If a role is being granted, then it must be common, and if an object privilege is being granted, then the object on which the privilege is granted must be common.

Roles and Privileges Granted Commonly

A common user or role may be commonly granted a privilege (CONTAINER=ALL). The privilege is granted to this common user or role in all existing and future containers. For example, a SELECT ANY TABLE privilege granted commonly to common user c##dba applies to this user in all containers.

A user or role may receive a common role granted commonly. As mentioned in a footnote on Table 18-6, a common role may receive a privilege granted locally. Thus, a common user can be granted a common role, and this role may contain locally granted privileges. For example, the common role c##admin may be granted the SELECT ANY TABLE privilege that is local to hrpdb. Locally granted privileges in a common role apply only in the container in which the privilege was granted. Thus, the common user with the c##admin role does not have the right to exercise an hrpdb-contained privilege in salespdb or any PDB other than hrpdb.

See Also:

Oracle Database Security Guide to learn how to grant roles and privileges in a CDB

Grants to PUBLIC in a CDB

In a CDB, PUBLIC is a common role. In a PDB, privileges granted locally to PUBLIC enable all local and common users to exercise these privileges in this PDB only.

Note:

Every privilege and role granted to Oracle-supplied users and roles is granted commonly except for system privileges granted to PUBLIC, which are granted locally. This exception exists because you may want to revoke some grants included by default in Oracle Database, such as EXECUTE on the SYS.UTL_FILE package.

Assume that local user hr exists in hrpdb. This user locally grants the SELECT privilege on hr.employees to PUBLIC. Common and local users in hrpdb may exercise the privilege granted to PUBLIC. Users in salespdb or any other PDB do not have the privilege to query hr.employees in hrpdb.

Privileges granted commonly to PUBLIC enable all local users to exercise the granted privilege in their respective PDBs and enable all common users to exercise this privilege in the PDBs to which they have access. Oracle recommends that users do not commonly grant privileges and roles to PUBLIC.

Grants of Privileges and Roles: Scenario

In this scenario, SYSTEM creates common user c##dba and tries to give this user privileges to query a table in the hr schema in hrpdb. The scenario shows how the CONTAINER clause affects grants of roles and privileges. The first column shows operations in CDB$ROOT. The second column shows operations in hrpdb.

Table 18-7 Granting Roles and Privileges in a CDB

| t | Operations in CDB$ROOT | Operations in hrpdb | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

t1 |

SQL> CONNECT SYSTEM@root Enter password: ******* Connected. |

Common user |

|

|

t2 |

SQL> CREATE USER c##dba

IDENTIFIED BY password

CONTAINER=ALL;

|

|

|

|

t3 |

SQL> GRANT CREATE SESSION TO c##dba; |

|

|

|

t4 |

SQL> CREATE ROLE c##admin CONTAINER=ALL; |

|

|

|

t5 |

SQL> GRANT SELECT ANY TABLE TO c##admin; Grant succeeded. |

|

|

|

t6 |

SQL> GRANT c##admin TO c##dba; SQL> EXIT; |

|

|

|

t7 |

SQL> CONNECT c##dba@hrpdb Enter password: ******* ERROR: ORA-01045: user c##dba lacks CREATE SESSION privilege; logon denied |

|

|

|

t8 |

SQL> CONNECT SYSTEM@hrpdb Enter password: ******* Connected. |

|

|

|

t9 |

SQL> GRANT CONNECT, RESOURCE TO c##dba; Grant succeeded. SQL> EXIT |

|

|

|

t10 |

SQL> CONNECT c##dba@hrpdb Enter password: ******* Connected. |

Common user |

|

|

t11 |

SQL> SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM hr.employees;

select * from hr.employees

*

ERROR at line 1:

ORA-00942: table or view does

not exist

|

The query of |

|

|

t12 |

SQL> CONNECT SYSTEM@root Enter password: ******* Connected. |

Common user |

|

|

t13 |

SQL> GRANT SELECT ANY TABLE TO c##admin CONTAINER=ALL; Grant succeeded. |

|

|

|

t14 |

SQL> SELECT COUNT(*) FROM

hr.employees;

select * from hr.employees

*

ERROR at line 1:

ORA-00942: table or view does

not exist

|

A query of |

|

|

t15 |

SQL> GRANT c##admin TO c##dba CONTAINER=ALL; Grant succeeded. |

|

|

|

t17 |

SQL> SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM hr.employees;

COUNT(*)

----------

107

|

The query succeeds. |

See Also:

Oracle Database Security Guide to learn how to manage common and local roles

Overview of Common Audit Configurations

For both mixed mode and unified auditing, a common audit configuration is visible and enforced across all PDBs. This configuration can include actions, system privileges, and only common roles and common objects. You can apply this configuration only for common users. An audit configuration that is not common is local, which means it applies only within a PDB and is not visible outside it.

Note:

Audit initialization parameters exist at the CDB level and not in each PDB.

PDBs support the following auditing options:

-

Object auditing

Object auditing refers to audit configurations for specific objects. Only common objects can be part of the common audit configuration. A local audit configuration cannot contain common objects.

-

Audit policies

See Oracle Database Security Guide for comprehensive information about audit policies. Audit policies can be local or common:

-

Local audit policies

A local audit policy applies to a single PDB. You can enforce local audit policies for local and common users in this PDB only. Attempts to enforce local audit policies across all containers result in an error.

In all cases, enforcing of a local audit policy is part of the local auditing framework.

-

Common audit policies

A common audit policy applies to all containers. This policy can only contain actions, system privileges, common roles, and common objects. You can apply a common audit policy only to common users. Attempts to enforce a common audit policy for a local user across all containers result in an error.

-

A common audit configuration is stored in the SYS schema of the root. A local audit configuration is stored in the SYS schema of the PDB to which it applies.

Audit trails are stored in the SYS or AUDSYS schemas of the relevant PDBs. Operating system and XML audit trails for PDBs are stored in subdirectories of the directory specified by the AUDIT_FILE_DEST initialization parameter.

See Also:

-

Oracle Database Security Guide to learn about common audit configurations

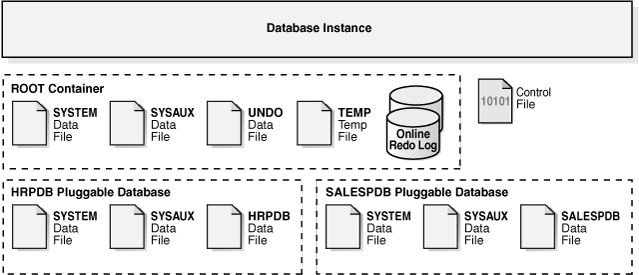

Overview of Database Files in a CDB

From a physical perspective, a CDB has basically the same structure as a non-CDB, except that each PDB has its own set of tablespaces (including its own SYSTEM and SYSAUX tablespaces) and data files. Figure 18-9 shows aspects of the physical storage architecture of a CDB with two PDBs: hrpdb and salespdb.

Figure 18-9 Physical Architecture of a CDB

Description of "Figure 18-9 Physical Architecture of a CDB"

As shown in Figure 18-9, a CDB contains the following files:

-

One control file

-

One online redo log

-

One or more sets of tempfiles

By default, the CDB has a single default temporary tablespace named

TEMPthat every PDB uses. You may choose to create a different default temporary tablespace. Only a temporary tablespace that you create while connected to the root can serve as a default temporary tablespace for the CDB. For an individual PDB, you may override the CDB-wide temporary tablespace by creating a local temporary namedTEMP, and then setting it as the default. -

One set of undo data files

In a single-instance CDB, only one active undo tablespace exists. For an Oracle RAC CDB, one active undo tablespace exists for each instance. Only a common user who has the appropriate privileges and whose current container is the root can create an undo tablespace. All undo tablespaces are visible in the data dictionaries and related views of all containers.

-

A set of system data files for every container

The primary physical difference between CDBs and non-CDBs is the system data files. A non-CDB has only one set of system data files. In contrast, the root and each PDB in a CDB has its own

SYSTEMandSYSAUXtablespaces and its own complete set of dictionary tables describing the objects in itself. -

Zero or more sets of user-created data files

In a typical use case, each PDB has its own set of non-system data files. These data files contain the data for user-defined schemas and objects in the PDB.

The storage of the data dictionary within the PDB enables it to be portable. You can easily plug and unplug a PDB into a CDB.

See Also:

-

Oracle Database Administrator's Guide to learn about the state of a CDB after creation

Privileges in this role are available to the grantee only in the container in which the role was granted, regardless of whether the privileges were granted to the role locally or commonly.

Privileges in this role are available to the grantee only in the container in which the role was granted and created.

Privileges that were granted commonly to a common role are available to the grantee across all containers. In addition, any privilege granted locally to a common role is available to the grantee only in the container in which that privilege was granted to the common role.